|

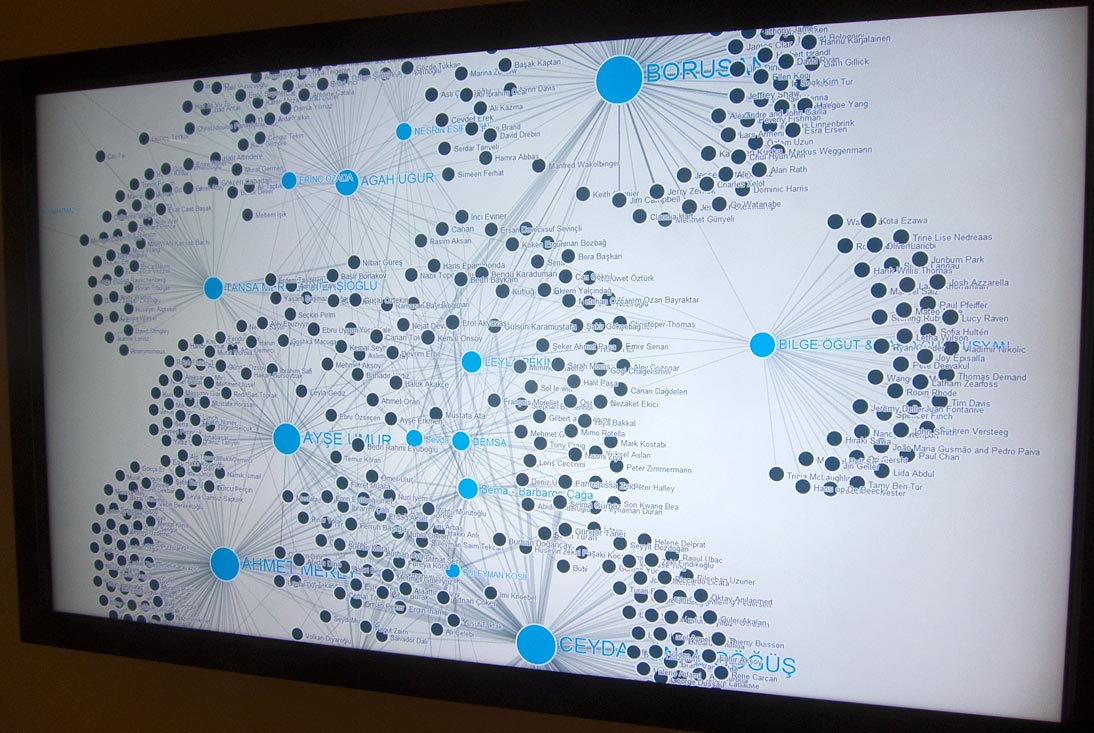

| Artist Collector Network by Burak Arikan |

All those articles about the booming art scene

in Istanbul… One after another, pouring over the Western newspapers was not the

reason why I chose to live in Istanbul. I personally didn’t choose to live

here; it was an accident caused by another accident that little did I know how

much it would shape the course of my “career”. I did not have a career or even

an aspiration to, and started writing about contemporary art from the Middle

East out of entirely personal motivations.

At a point it might have even been a political

project to approach difficult questions in a region in turmoil from the

margins. A few days ago I went to see for the second time the show “Aeolian” at

Rodeo Art Gallery and could spend a good deal of the afternoon with Emre Huner,

the artist behind the show. Between one cigarette and another, the conversation

drifted away from the actual artworks into some travel memories, shared

frustrations and “art talk”.

“Art talk” is not a metaphor for those profound

and challenging conversations that many people imagine that artists have with

each other and with the rest of the acolytes in the art religion: Gallerists,

dealers, critics, curators and what not. Art talk actually is the small talk

that happens in the corner of exhibition openings: A little gossip, a little

complaining, and always making sure to assert how one does not belong to the

art world, how one actually hates the art world.

“I will not attend any openings anymore”, I

said a couple of weeks before, finding myself intoxicated by this micro-cosmos

of celebrities and the rituals associated with this complex network of

creativity, business and frivolousness that is called nowadays the art market.

A lot of kissing and hugging, a lot of drinking, a lot of flirting, and in the

end of the day, a great sense of isolation that makes us cling to each other, in

order to feel less the pressure of the world against this undefinable

profession.

And during six weeks I stayed mostly at home,

thinking about this great arts scene in Istanbul that everyone is talking

about. I felt that I needed a critical distance from the noise of the “scenes”

in order to assert that I do not belong there, that I am special, that I am

different, that I am independent. This is not real. This is not real. I said to

myself over and over as I leafed through the pages of endless exhibition

catalogs and books trying to feel inspired to write about art.

A few weeks before, while visiting the studio

of another Turkish artist, Hale Tenger, we talked about what it is that “inspires”

you to write about art, and our conclusion was vaguely similar: We do not read

art texts or art books. The raw materials to approach contemporary art

precisely that, raw, things like history books and novels, films you loved,

conversations with friends, the daily news in this endless show of parody and

horror called the Middle East.

Art writing has a tendency to say very little,

to prevent the forming an opinion, to discourage judgment and more than

anything, to obscure some artworks that are actually already obscure and

perhaps not really good. There’s such a thing as bad art, there’s such a thing

as awful exhibitions, there’s such a thing as wrong curatorial practices. But

we don’t talk about that in Istanbul. This great arts scene that everyone is

talking about exists only in the mind of some writers elsewhere.

It’s not that art is bad… Or maybe some of it

actually is, but it’s more something like this: We live at the center of this

gigantic and formless mass called Istanbul but we are not even in or from

Istanbul. We have a tiny prison called Beyoglu, that exists in an altogether

different dimension and if the end of the world would come, we wouldn’t hear

about it for days, being so busy attending openings or recovering from

countless glasses of wine from three different openings in the same night.

And we live in this prison willingly. I’m

calling it a prison because in spite of being subject to constant abuse,

impossible traffic, long distances by foot, insane rent prices and asshole

landlords, pollution, endless hills, impossible noise, and a rather

deteriorated quality of life, we refuse to leave and it is common to hear

friends saying that leaving Beyoglu is like going overseas. Some of us even go

abroad more often than outside this prison with leisure facilities.

Last night on a taxi with Derya Demir, a

gallerist friend, dying from a headache caused by an exhibition the night

before, traveling far out to Etiler to attend another opening, we heard

ourselves saying “this shit better be good, if we’re going this far already”.

And never mind, it was great, but then you begin to understand that Beyoglu is

also a portable concept: The same ten people move everywhere in pairs and

groups. Discuss each other. Love each other. Drink each other. List goes on.

Not that there’s anything wrong with that. In

the end of the day, beyond the petty fights and the endless gossip about who

pays and who doesn’t, who is good and who isn’t, which gallery has this or that

issue, people in Istanbul I find, are a lot more open and kind than in many big

cities. It doesn’t take you too long to get to know the “scene”, and whether

you want to be part of it or not, it is a personal choice, the doors are

somehow always open.

Of course this applies to expats more than it

does to other Turks. But yet Istanbul is not something you are born into,

Istanbul is something that you become. It is hard to tell when this actually

happens, but one day you wake up and realize you have acquired the imaginary

citizenship of the imagined crossroads. But no crossroads in Istanbul really

exist. Mari Spirito, a partner in many day and night adventures, has always

told me this isn’t crossroads but purgatory.

A lot of people actually end up in Istanbul

like I did, by accident. Then one day they wake up and realize they’ve been

here for ten years. Beyoglu takes everything from you: Your money, your

patience, your liver, your time, and guess what? It does not give you back anything. You need to reclaim energy from the city on your own. Usually this

energy is best reclaimed in groups, sitting for tea at the London Hotel at 4 pm,

which usually becomes whiskey at 4 am in the blink of an eye.

But wait, it does sound like the perfect

setting for an art scene, doesn’t it? Well, it’s not. Art does exist in

Istanbul and I kid you not, there’re many artists, in all degrees of ages,

accomplishment, style, technique, concept, etc. But there’s no art scene here.

Scene would immediately require two things: The first would be an audience for

art outside the “experts” and also with an audience, comes the dialogue about

art. None of them are present in Istanbul.

Artists and galleries work mostly in isolation,

in isolation from each other especially because everyone is so afraid to

criticize. There’s no criticism, because hey, we’re hot-headed Middle

Easterners and take everything personal. The only thing being discussed is

actually personal traits of this and that artist, of this and that gallery

owner, but it is never about the works, it is never about the shows. It is

never about anything.

Many artworks are constructed in

self-referential ways and are more about a personal narrative. Sometimes people

tell you “you don’t get it, do you?” but who the hell really gets art? If there

comes a day that an art writer comes to “get art”, that day he should drop out

and go to work in finance. And some people do write about art, no question

about that, both in Turkish and English. But the reviews are not positive or

negative. The reviews are about art reviews, actually.

In our conversation, Emre Huner was telling me

about how in an interview he was asked his opinion about the booming art scene

of Istanbul, and he thought that maybe it would be better to talk about the

articles about the booming art scene than about the actual thing. Turkey is a

country with identity issues, and this is surprise to nobody, that still

belongs to a larger region where the making of art is at best problematic.

Without a strong tradition in arts – and I’m

not making this up, Orhan Pamuk held the same view – there seems to be the

question of the foundations of art. Ottoman painting is hardly the inspiration

for contemporary art and whatever Turks and Lebanese call modernism has next to

nothing to do with modernism, it is a late classical realism profoundly

embedded in colonial and imperial narratives. To say “go back to basics” in

Turkish art is nothing short of an oxymoron.

It seems to me at times as if some young

artists are running too quickly too conceptual art without the mastery of at

least one technique and while this is the actual standard practice in the

Western world, openly promoted by art schools, it does not make it any less

lame. The relationship of Turkish art to the surrounding is very fragile; no

discussion whatsoever with Arab art and somehow at the margins of European art.

But hey, it’s 2013, who cares where art is from? All art is art, right?

This would be fine weren’t it the case that

certain artists are being bought, exhibited, collected and discussed not

because all art is art but because they’re Turkish. The well-meaning Western

collector wants to see the cute little things that we produce you here in spite

of being abused, tortured, jailed, molested, brainwashed. In the meantime,

parties go on unmolested in Beyoglu seven days a week without giving a single

thought to any of that horrible present we market ourselves through.

And you know well that nobody goes to openings

except us the same ten people who get smashed together three times a week. And

this is great in a way, we’re all becoming sort of friends, sort of professional

acquaintances, sort of buddies, because most of us are actually quite young. In

the end of the day one of the risks associated with an “art career”, is that

our private life is also our professional life. Our most intimate belongings are

on show for display and sale.

So everybody talks about this important artist,

that important curator, that important gallery, that important critic.

Important, important, important. Whatever. No one gives a damn. Not Turkey, not

Istanbul, not Beyoglu. Most people don’t even know we actually exist. We’re not

important to anybody, except ourselves and each other. This isn’t to say we don’t

do good stuff, but art in Istanbul – and the Middle East – is not part of the

public sphere. It is not shaping it in anyway.

And this is not because artists aren’t

interested in this – some of them clearly aren’t, but that’s a different story,

but because we happen to live in a very oppressive country in a city in which

outside our bubble an ocean of covered heads thrives without any need whatsoever

for your fancy ideas. And hell, there’s no freedom here, and that’s why we are

drinking three times a week and hiding in your exhibition salons. There’s no

alternative. But we never talk about this.

At every exhibition the same happens… The same

dude comes, gives you the same kiss, tells you how nice the show is, drinks

your wine, networks a bit and then leaves to catch the next shame train into

the same five bars. Rinse and repeat. That is not to say this city isn’t great,

and actually it is full of miracles, it gives you more space to breathe than

any Arab country ever will, and it can be quite comfortable if you do it right.

And the isolation is such that we aren’t

bothered by the art world even. This weekend at the super fancy opening at

Borusan, all the Beyoglu kids stick to each other even though there were quite

a crowd, some important curators, some very interesting artists, and why not

say it, a super high-profile crowd including some society ladies. But that didn’t

bother us at all. We weren’t there to talk to anybody, but ourselves.

“Turkish art is problematic”, tells me Cynthia

Madansky, an American artist recently shown at SALT. And what does that even

mean? I think that’s a way to say Turkey is problematic. At times this country

reminds me of Latin America. So proud of a certain history which more than

anything is imagined, and at the same time wiping out the traces of the real

history. A Lebanese friend is all excited about coming to Istanbul to see

Istanbul Modern. I’m a lot less.

The building is great, the view is fantastic

and the coffee shop is super hype. The artworks… Well, let’s not talk about it.

Things look a lot fancier than they actually are, and if you’re in the wrong

place at the wrong time, you find yourself across botoxed bimbos in leopard

heels carrying five kilos of silicon in the most upscale dinners as the

prospective clients for your artworks. And this isn’t bad; this is just life,

and what galleries, dealers and what not have to do to keep sponsoring free

wines.

We shouldn’t be troubled by it; we just have to

keep going business as usual. There’s nothing wrong with living in the bubble,

but if we’re already at it, maybe it’s time to have an actual discussion about

art, since there’s just us after all… It doesn’t have to be intimidating,

really. It’s just that well… The art is getting a bit boring, and sure as hell

there’re clients for boring art too, but what a pity it would be to be part of

this batshit crazy city and do art in isolation.

No comments:

Post a Comment