For T.A.

[L'empire des lumières, 1954]

“It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances. The mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible.” –Oscar Wilde

A jocular story was told about the Belgian painter René Magritte: He went into the grocer’s shop intent on buying a few slices of the traditional Dutch cheese; when the saleswoman moved on to grab the block on cheese on the display to cut the slices for him, he objected. What is the problem? Asked the saleswoman. Magritte responded that that block of cheese had been stared at the whole day[1]. This anecdote sums up succinctly the impetus of the eye in Magritte’s paintings: Objects transform into other objects merely by seeing them. He aimed not at an eye of knowledge or interpretation but at a Cyclopean eye – once confidence is lost in optical illusions, all what remains is a fleeting moment of anguish in which the impossible dissolves into the possible.

The temptation of the impossible is not realized in the absent subject of abstract painting in which only the vague voice of consciousness blends in with the brush of the painter – as for example in the paralyzing color-fields of Mark Rothko – but in visualizing wholly visible and real objects as impossibilities. The painter roughly classified as a surrealist – perhaps because of a period convention and association with prominent names of the movement – defies the illusion of the surrealists in positing that what interests him is not the world of dreams, for two reasons: Firstly, dreams have a time-movement quality that is only available to films; secondly, for Magritte the dream in painting is trivial and unimportant if it is not fully tangible.

What Magritte wanted in his paintings was not to translate dreams, but rather to present a world in which rather than sleepwalking through images and representations, one stands before primal objects, at an interlude in which interpretation is not possible. Full wakefulness without reference to dreams as if in a procedure similar to that of Joyce’s Finnegans Wake: “Through all these scenes glide similitudes that no reference points can situate. Translations with neither point of departure nor support.[2]” What does it mean to be awake? That seems to have been the real question that haunted Magritte. It is not persons or landscapes what he wanted to see but objects as they appear to us without standards or possible interpretations of reality.

Paul Cézanne comes to mind when he says: “Well, no one has ever painted the landscape, man absent but entirely within the landscape”. Is it perhaps a re-configuration of both the still-life since its appearance in the Dutch paintings of the 16th century and of the pictorial space of the Italian 15th century? “The lived object is not rediscovered or constructed on the basis of the data of the senses; rather, it presents itself to us from the start as the center from which the data radiate.[3]” Magritte’s interest was not in objects as compositions but in doing what his predecessor Manet would do – and whom he deconstructed in his own work – not in inventing non-representative painting but rather picture objects or painting objects[4].

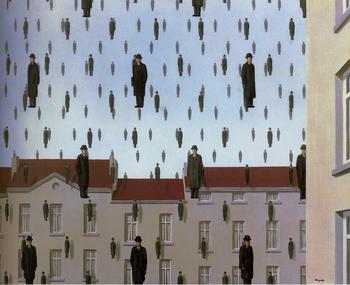

[Golconde, 1953]

Magritte wanted to represent things: “I just painted the paintings I thought to paint and did it. There’s nothing behind it. It is the picture I wanted to paint, and you see it. You don’t have to look for a symbol in there.” Franz Kafka, in his posthumously published Blue Octavo Notebooks (set to music in 2004 by German-British composer Max Richter), had a literary image for the kind of wakefulness that Magritte demanded: “Everyone carries a room about inside them. This fact can be even proved by means of the sense of hearing. If someone walks fast and one pricks up one’s ears and listens, say at night, when everything round about is quiet, one hears for instance, the rattling of a mirror not quite firmly fastened to the wall.”

What is this mirror? What can be seen through the mirror or through the window?Schlegel had the idea that the problem with mirrors or windows is that they become obstacles between spectator and landscape, however, there’s no real landscape in Magritte because he has left the pictorial space and is not content with representing. Sarah Kofman tells us in reference to a painting by Greuzedepicting a crying girl and entitled “The Broken Mirror”: “The bird is always already flown, the mirror is already broken, cracked, and it is this shattering of meaning that the girl is crying over –the loss, along with the mirror and the bird, of all reference and thus of all discourse.[5]”

Kofman tells us that the painting does not mean to say anything at all and explains further: “Between the figurative order of the painting and the discursive order of language there exists a gap that nothing can bridge.[6]” Similar is the demand of Magritte when he calls himself an objective painter and rejects both the arbitrariness and the lack of distinction between crass objects and art objects in modern art – exemplified by the practices of Dada, Surrealism and Duchamp – and yet says: “Don’t search for hidden images in my paintings.” He considered himself more of a thinker in terms of images than a painter and objected the notion of art for art’s sake: “There is thus no art for pleasure’s sake alone. One can manufacture objects that are pleasurable by linking ready-made ideas in a different way and by presenting forms that have been seen before.[7]”

Magritte’s point of departure, if any, was a painting by Giorgio Chirico, “Chanson d’Amour”, a proto-Surrealist academic study in free association of images that opened a possibility distinct to that of the totality that was being practiced and experienced by the painters of his time. In between the objects themselves, there seems to be a lot of empty space, a room of anxiety and uncertainty. Magritte is the painter of the absolute absence, faces covered with blankets, objects that come to life only in their dislocation, and life that emerges out of a syntactic chaos that is yet composite: “The presence and absence of the painter, his proximity towards his model, his absence, her distance, finally all of this would be symbolized by that empty space.[8]”

It is said that Monet and Magritte’s project of painting the impossible culminated at the limits of Impressionism when touching at the edges of the inhuman character of things to bring forth the human world of alienation, highlighting a devotion to the visible by contrast[9]. This is the courage of his art, as Hélène Cixous speaks of Monet: “And the greatest kind of courage? The greatest kind of courage. The courage to be afraid. To have the two fears. First we have to have the courage to be afraid of being hurt. We have to not defend ourselves. The world has to be suffered. Only through suffering will we know certain faces of the world, certain events of life: the courage to tremble and sweat and cry is as important for Rembrandt as for Genet.[10]”

This is why Magritte finds redemption in the wholly and absolutely visible: “I think that the world is a mystery and we cannot say anything about a mystery. It cannot be a subject of fear or hope.”

[Le Retour de Flamme, 1943]

[1] Ellen Handler Spitz. Museums of the Mind: Magritte’s Labyrinth and Other Essays in the Arts (New Haven: CT, Yale University Press, 1994): 48-49.

[2] Michel Foucault. This Is Not a Pipe (Berkeley: CA, University of California Press, 2008): 52.

[3] Maurice Merleau-Ponty. “Cézanne’s Doubt” in The Merleau-Ponty Reader: Northwestern University Studies in Phenomenology and Existential Philosophy(Evanston: IL, Northwestern University Press, 2007): 75.

[4] Michel Foucault. Manet and the Object of Painting (London, Tate Publishing, 2012): 79.

[5] Sarah Kofman. “The Melancholy of Art” in Selected Writings (Stanford: CA, Stanford University Press, 2007): 210-211.

[6] Sarah Kofman. 2007: 211.

[7] Maurice Merleau-Ponty. 2007: 78.

[8] Michel Foucault. 2012: 77.

[9] Maurice Merleau-Ponty. 2007: 70.

[10] Hélène Cixous. “The Last Painting or the Portrait of God” in The Continental Aesthetics Reader (London: Routledge, 2000): 591-592.

No comments:

Post a Comment