["Assassinat de Samir Kassir au Liban", oil on canvas, Romain Chabin, 2005]

Sometimes one would think that Lebanon is too demanding. It demands too much from those who ever want to love it. Anyone who has been a journalist in the second Lebanese republic, knows well, to paraphrase the late Samir Kassir, that this republic has proved to be as pusillanimous as the first. Being a journalist or a writer in or about the land of Amin Maalouf, Nadine Labaki and Hassan Nasrallah, is something that always begins with great excitement and one can hear young correspondents growing intensely frantic over terminology such as “war-torn”,“conflicted”, “restless”. The truth is that Lebanon is an endless supplier of intellectual pornography that is consumed just as avidly.

But there are other phases too. After the excitement comes the agony, and with the agony the disenchantment, the questions, the what if’s… One tries to find his own comfort zone, and since modern history is hardly a candidate for this, there is always the uproarious humor, the extravagant laughter and intense feeling of uncertainty that Lebanon produces. And like the Lebanese and with them, one laughs, one laughs because there is nothing else to do. Laughter is seemingly meant to stage hope in a truer and far more terrifying way. Laughter seems to be an affirmation of life, whereas tears are simply a demonstration. You’re doing your job. This is what people do. They write stuff. They pack. They leave. They forget the stuff they wrote.

On any night one can stroll around Beirut, and sense its infinite possibilities. Infinite also means unmovable, somewhat eternal, fixed and unchangeable. There are always the parties; everyone talks about the parties, as if it was a secret society that is not so secret after all, and half the population of Beirut has had honorary membership in it at a point. From the outside it seems as if there were this spectacular resilience and sense of life. With time one also learns that they’re only waiting. You learn to wait too. What could I have done if I were born Lebanese? You ask yourself that too. Having Lebanese ancestry doesn’t help. Of course you know you’re simply being permitted to watch. You can’t take part.

You tell yourself: I love Lebanon. I love the Lebanese. But you don’t. At least you don’t want to. Why on earth would you want to fall in love with disaster? Maybe you love yourself in Lebanon. It makes you feel brave, powerful, informed and more than anything, playing with death a little bit. It’s the uncanniest flirting. But this isn’t only about wars. Whoever has lived – and especially whoever grew up – in awar zone knows well that life still goes on. What is really terrifying isn’t the strength of war, but the fragility of things. Stuff still happens, you know, weddings, accidents, falling in love, beauty contests. Those are the bigger questions: How? The terminology changes again. One stops saying “war-torn”, “conflicted”,“restless”. One goes back to basics: “beautiful”, “ugly”, “good”, “bad”.

Talking with a Lebanese musician about Lebanese art, he says something revealing about what one sees in the country: “This weekend for example in the neighborhood where I live – Achrafieh – they implemented for the first time a no-car zone. For twelve hours no cars can drive in this big crowded neighborhood, so that people can enjoy walking their dogs, discovering the architecture of the old houses, biking in clean empty streets, etc. while an hour drive from here people are shooting at each other because they decided they don’t like each other, or because they are from a different sect! That for me is contemporary art by itself. We are a big piece of contemporary art; good or bad.” A big piece of art, art is like that. Crazy. Now you can sleep better.

In the early morning of September 14th, one wakes up and scans through the news. Maybe something interesting? Writers are like that. Pickpocketing. Surprise me once more, life. A traffic accident: “A Volvo car trailing at an excessive speed hit the back of a truck on Jal El-Dib highway leading to the death of the driver, citizen Wajih Raed Al-Ajouz.” Name sounds familiar. One doesn’t really want to think about it. How many times did one write somebody died here, somebody died there. Death acquires singularity. Wajih Al-Ajouz was different; he was somebody, someone you could recall. You had spoken to him. Only the day before. You had laughed about something. A few hours later the confirmation of his death arrived.

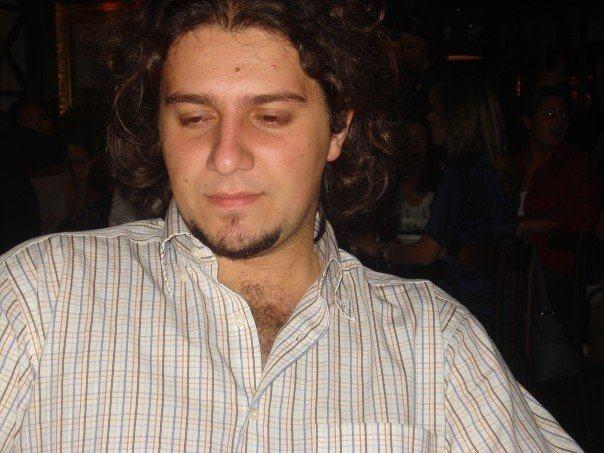

It was a cold breath. One of those moments in which you reproach yourself for loving the Lebanese, or particular Lebanese. This could happen to one of them, you know. It’s not that this couldn’t happen anywhere else, but simply that in such overflow of life and circumstances, stuff becomes bigger, so much bigger than historical events. You thought of the musician, and said to yourself, how I wish that Lebanon was just that, a piece of art. A piece of art that you can cover with a sheet and not see it anymore once it turns ugly. A young man, 25 years old, a journalist, reckless atheist and advocate for freedom of speech, a liberal flirting often with debauchery and a researcher for the foundation that bears the name ofSamir Kassir.

These things sound commonplace, but they’re particularly enjoyable in Lebanon. The privilege of free, unrestrained, uncensored and intimate conversation. The immense responsibility of freedom. That’s how one talked to Wajih Al-Ajouz. This young man, who disappeared just like that, on a cold morning, he loved freedom and life. Something that cannot be said about Lebanon. Critic of censorship, supporter of freedom of expression, a believer that embodied what he believed in such a way that it was impossible to do what one usually does: Look the other way. He liked looking at life right in the face. But Lebanon demands too much. How much more can be given to it? How long more will its enemies prosper and live? No one knows.

Ayman Mehanna, the executive director of Samir Kassir Foundation’s SKeyes told Lebanese paper “The Daily Star": “He will be greatly missed. Today we are gathering Wajih’s writings and pictures, and we want to publish a booklet in his honor. Wajih worked on monitoring all forms of violations of press and cultural freedoms in Syria and was a point of contact for the SKeyes correspondents in Syria.” How sorely missed is and will be the privilege of friendship, of political bravado, of sincerity and of free-thinking in a part of the world so consumed by the radical opposites of all that. As usual in Lebanon, the news report ended with: “It is worth noting that the driver of the truck continued driving and fled to an unknown destination.”

“Keep your mind in hell, and despair not” was a saying of a little known Orthodox monk quoted in the opening of “Love’s Work”, the parting memoir of the British philosopher Gillian Rose, whose intensity and reckless sincerity can only be matched by the likes of Al-Ajouz. One imagines him speaking through Rose from wherever he is now: “I will stay in the fray, in the revel of ideas and risk; learning, failing, wooing, grieving, trusting, working, reposing – in this sin of language and lips.” In the meantime, Lebanon keeps demanding, demanding, demanding, consuming, and we keep letting it happen. Gillian Rose sums it up succinctly: “I’ve told you the tale, the Midrash is not beautiful, it is difficult.”

[Wajih Al-Ajouz 1987 - 2012]

A moving tribute to Al-Ajouz, published by a Lebanese blogger, "See you in Beirut, Wajih".

No comments:

Post a Comment